Up & to the right

Money

Ah, yes, money. Some say money makes the world go round. Some say it can be the root of all evil. The Bible, the Koran, the Torah (and probably other scriptures that have been around for thousands of years as well) all allocate plenty of time and effort to attempting to define money’s role in society, and for good reason. Money can represent everything from freedom to slavery or anything in between.

Thousands of art works, poems, songs and books have addressed this at length. And depending on who you ask, speaking about it in too much detail can be considered taboo. Whatever words I choose to either serenade or criticize the concept of money today, I wouldn’t quite be able to do its historical significance enough justice. So let’s just say that money can be important and examine it a little closer. Maybe it can even help with choosing the best asset classes to invest in.

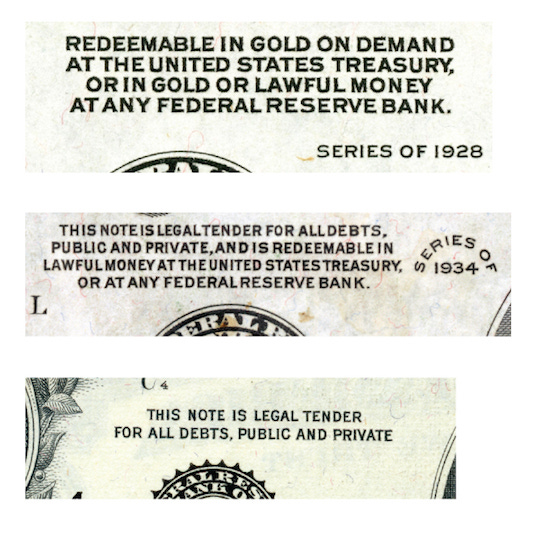

The characteristics of money as we know it are durability, portability, divisibility, uniformity, acceptability and having a supply that can only be increased by certain actors. For example, if certain banks create new money, it’s a systemic necessity, and if I do it, it’s illegal counterfeiting.

The role of money is usually split up in 3 parts:

unit of account (we usually denominate value and count in our local currency. ‘My net worth is X€’)

means of exchange (some of the aforementioned features make money great for trading different goods & services. For example, you can trade €$£ for a pizza, without directly offering your own goods & services.)

store of value (fiat currency doesn’t expire, and could therefor theoretically be viewed as a store of value that you can still use tomorrow, if you save it today)

But is that last part entirely true? Is it truly reasonable to expect that something with all these other useful characteristics could also retain its full purchasing power over time, especially given the fact that its supply is systematically increased? Can something be both a great means of exchange ànd a good store of value? Has this ever been the case in history?

If you speak to children, it seems that means of exchange is most the intuitive use case (‘let’s play store, I sell you a banana for 2 plastic coins’), later followed by unit of account (‘my allowance is 10€’). Using fiat money as a store of value has never been ‘a thing’ at any point in history, as far as I’m aware.

A few bonus questions to add some, hopefully somewhat charming, childlike curiosity: if new money is created, what exactly is being created? New goods & services? Or something else? If we can print a few trillion to offer support in a pandemic, why can’t we add money to the money supply to solve world hunger or disease in other continents? Who decides this? Based on what - science or ideology? Or why pay taxes if we can just print money? And who is the money owed to? How did they get that money originally? What happens if we pay the money back, does it reduce the money supply again? What happens if we don't pay the money 'back'?

Only loosely related, but it reminds me of this internet gem.

As this is my blog, I’ll permit myself to be quite forward. I think central banking is an activity that is much too obscure and circumlocutory compared to how impactful it is, vastly outgrowing its original scope. Run under the guise of independence and, whether intentional or unintentional, resulting in record amounts of debt and inequality - and it’s not like central banking has always existed in its current form, either.

Yes, these childlike questions are actually not that objectively easy to respond to. Could you even imagine if they were? That would potentially be an even crazier situation.

Aside from the (very) obvious (and difficult to rebut) case pleading for considerably more transparency about the money supply given how pivotal its allocation can be, it’s not like I have an immediate alternative. But to emphasize this tangent, I feel pretty strongly that monetary policy has vastly more overlap with religion than with science.

It appears that -for some- the more years of academic study about said policies one has invested their time in, the more convinced they can become of their relevance and dubious claim to modernity, backed by a progressively complex jargon.

It makes me a little bitter. Despite ample practical evidence to the contrary that can be found in an increasingly devastating and unfair reality, a new normal sometimes seems to have come about. Quasi-sophisticated knowledge that should theoretically have led to a deeper and more objective understanding of a monetary system aiming to support well-being and increasing stability, has mostly evolved into an awkwardly self-referential doctrine. A doctrine that many in power urge to keep an uncompromising belief in, as it creates the status quo, albeit with the grotesque privilege of not having to take any tangible responsibility for its glaring imperfections. A real-time experiment, almost by definition, portrayed as a necessity. But for who?

Ah, the relief that rant makes me feel. Had to be done. But questioning aside, let’s look at some numbers. I genuinely don’t want to take your readership for granted.

M2 is a measure of the money supply that includes cash, checking deposits, and easily-convertible near money, denominated in billions. M2 is a broader measure of the money supply than M1, which just includes cash and checking deposits. The above chart is the chart of the money supply. Without judging that notable uptick in 2020 per se, this makes for an interesting exercise: charting assets versus M2. Because fundamentally, this is what we are trying to outperform when we are investing.

Trying to beat inflation, of course. And even though inflation and the money supply are not at all the same thing, keeping an eye on an asset’s performance against M2 can give you better odds to actually beat inflation, as it is even harder to outperform M2.

One can beat inflation without beating M2, but one cannot beat M2 without also beating inflation.

For the sake of this thought experiment, one could also have chosen the balance sheet of their respective central bank and charted against that. It also makes for interesting outcomes as a balance sheet sometimes shrinks and M2 does not. But for the sake of this ‘exercise’, the point is more to underline the fact that inflation makes everyone a market speculator because they must invest in various assets and take calculated risks to keep pace with monetary debasement.

Keeping an eye on M2 might be more demonstrative of what not to do, than for actionable trading advice.

Let’s look at a few charts.

Average wages in the US, versus the money supply. Unfortunately, the trend is clear. Same goes for all other countries, with a few nuances here and there.

Even the Nasdaq is struggling to keep up with M2. It is up from the 2008 lows, but it has not made a higher high since its Dotcom bubble top. This is the Nasdaq, divided by M2:

Obviously some individual Tech names have managed to outperform M2 by a lot, but it’s still pretty crazy when you think about it, because the Nasdaq is one of the strongest indexes out there, if not the strongest. That means nearly all other indexes will have done worse. It also underlines that finding assets that beat M2 is likely optimal portfolio allocation. Now, of course, we also have to define time frames when speaking of trading and investing, which I haven’t done yet. When day trading, M2 probably doesn’t matter at all. When swing trading (weeks to months), maybe it could matter just a tiny bit, if only to help seek out the strongest performers within an Index.

But for those simply wanting to aid their future retirement, largely following a buy & hold approach, perhaps even strategically rotating between some strong trends here and there, charting against M2 can potentially make a notable difference over time.

It can help create a simple filter between assets: which ones have made a higher high versus their 2007 peak, and which ones haven’t.

Gold. Disappointing for the long term investor. The amount of money in the world has gone up a lot, but Gold has been unable to obtain a bigger piece of that growing ‘money pie’, even though it is a scarce physical asset. Noteworthy. An unkept promise on a chart.

Tesla - didn’t exist in 2007/2008 but in a much stronger trend than the Nasdaq.

Bitcoin also absolutely crushed M2 since its existence, now with a little less momentum, but clearly one to keep keeping an eye on.

Taiwan Semiconductors. Surprisingly strong historically. I didn’t know that either:) Where does it go from here though?

Is it even possible to outperform M2, without actively trading, seeing as even holding the Nasdaq means struggling to do so? Maybe through stock-picking combined with some basic trend-following strategies.

Lastly, always good to keep an eye on the Euro/Dollar rate. The EURUSD has clearly been trending down since 2008 and holding cash in dollars would have been the superior play. Now, a basic observation is that for the last years, price has not gone below circa 1.05, and on the other side, has difficulty to sustain above 1.2 for very long.

Probably a good idea to keep an eye on what happens if one of those two levels ever get broken out of again and what this means for the geopolitical context of the two currencies.

To be continued. I think the next two weeks could be pivotal for global markets as a whole and expect some opportunities to arise.

For my next posts, I’m hesitating between covering the Uranium investment thesis, the Elon Musk trying to buy Twitter saga, growing food shortage concerns, or the continued development of Central Bank Digital Currencies in combination with crypto’s role in mainstream politics. I’ll probably end up writing them all in the coming weeks/months, but if you have a preference, by all means let me know.